Artists encourage indigenous art to evolve using new techniques and materials

Artists discuss how Indigenous art has developed and why many do not have the same appreciation and access to mainstream galleries and museums as non-Indigenous peers.

PAGUATE, NM – Homes with flat roofs and exterior walls, hand-stacked from western New Mexico’s distinctive pale yellow mud-plastered limestone cluster around the main plaza in this Laguna Pueblo town.

One is more than 300 years old, a structure that has been repaired and supplemented with modern concrete blocks. A power line snakes in from a nearby pole and a satellite dish glints in the sun. The sturdy walls and roof are built with wooden beams that support waterproof roofing to keep the home warm and dry on a blustery spring day.

Welcome to Pat Pruitt’s house.

When visitors step through the simple wooden door, they see much more than just an old house. The living spaces are small — Pruitt said his entire family of five slept in the existing bedroom — but behind the original house lies an addition that tells a different story.

Three large rooms house the tools of Pruitt’s trade. There are lathes, drill presses, computerized machining tools known as CNC, milling machines, computer stations for design work and hand tools everywhere. Skateboard decks and other works of art brighten up the stark gray walls.

The largest room serves as storage space and, when boxes and crates are pushed to the walls, as a dining room for holidays. A second floor with more living space and a media room was a recent addition.

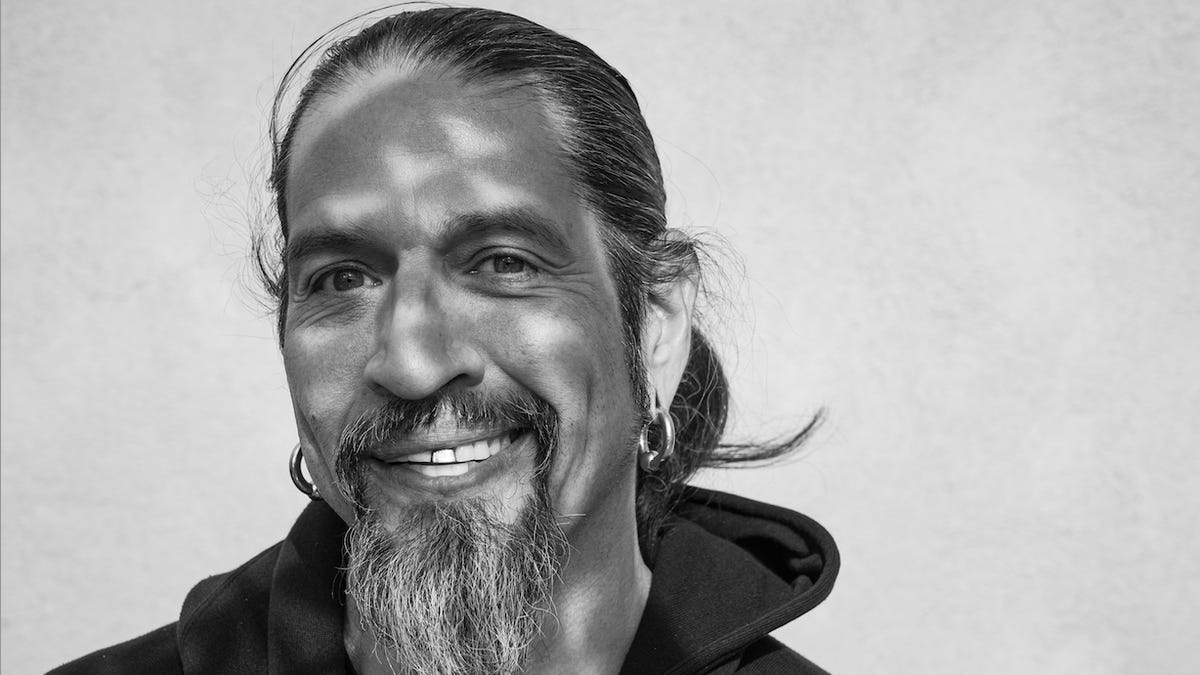

Like many native artists, Pruitt is a metalworker, although his preferred materials are not silver or gold, but stainless steel or titanium. Instead of intricately cut and inlaid stone, he prefers rougher industrial diamonds or shagreen to decorate his creations.

Pruitt is one of Indian Country’s art rebels, a group of indigenous artists who defy pressure from collectors, markets and some museums to stay within the lines of “Indian” art.

How an accident led to a career

Pruitt came to his life’s work literally by accident.

“I was involved in a pretty traumatic bicycle accident when I was 15,” he says. “It broke my skull, knocked out seven teeth and laid me out, so I had a pretty intense healing period.”

During his recovery, Pruitt became bored and asked a neighbor, silversmith Greg Lewis, to teach him the trade. Later, Pruitt collaborated with another Laguna artist, Charlie Bird. Between the two critically acclaimed artists, Pruitt acquired a solid foundation in metalworking.

Pruitt fell back on jewelry when he was a “starving student” at Southern Methodist University, where he studied mechanical engineering, in the early 1990s.

“The body piercing scene had come out of the underground and I got involved in the scene,” he said. “I thought, ‘I can make this jewelry.'”

What started as making pieces for friends quickly grew into a thriving business producing jewelry for the industry. It was also his introduction to stainless steel and titanium.

But Pruitt’s business stalled with the arrival of cheaper imported jewelry. So the ever-adapting artist pivoted: he forged a new path in Indigenous art by combining his early training in silversmithing with his newly acquired machining skills and interest in non-traditional materials.

The result was initially mixed. Like other artists whose work doesn’t scream “Indian,” Pruitt found collectors turning their noses up at his pieces. Some museums and galleries, thinking his work was factory-made, would not take it.

But they came about after he won one of the first Conrad House Innovation Awards at the Heard Museum Indian Fair & Market in 2007 for a rubber timing belt and stainless steel collar and leash set, “Lucky 13.” The award is named after the Navajo/Oneida artist who created expressive works of art in various media.

Since then, Pruitt has delved into the boundaries of metals like anodized titanium accented with stingray skin, rubber and industrial diamonds.

His career has allowed him to move back to the Pueblo, where he says he has been able to fulfill his role as a Pueblo man: serving in the community, helping with orchards and other agricultural activities, helping dig graves for funerals.

At the age of 50, Pruitt turned a new leaf: He returned to complete his bachelor’s degree at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“I went as far as I could without a degree,” he said. Pruitt also uses the time to continue growing as an artist. He will continue to work from his Paguate studio, improving his home little by little as he raises funds.

“They don’t give home improvement loans on the reservation,” he said.

And he is determined to control his destiny, including exhibitions. Pruitt terminated the contract for a proposed mid-career retrospective exhibition when the museum said his early work in body piercing art, which launched him into a life in metal-crafted art, would not be part of the show.

In windy Winslow, Arizona, two brothers lay out their route

The city that built the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad is a study in contrasts.

Home to about 10,000 people, Winslow, Arizona, is a little rough around the edges. Yet it boasts an elegant, restored Fred Harvey Company-era hotel, one of the few Amtrak stations in the state, bars, restaurants and plenty of places in the Victorian downtown to buy Route 66 memorabilia. Even the sculptor of the iconic bronze “Standing on the Corner,” which pays tribute to the Eagles song “Take it Easy,” has hawk T-shirts featuring his work.

But the small railroad town that is now a transfer point for the BNSF Railroad is also a mini-hub for another industry: artists. Several Native artists have settled in Winslow, or Béésh Sinil, the Navajo “Place of the Steel Rails.”

Two of those artists are brothers Marlowe and Yancey Katoney.

Marlowe’s picture textiles look nothing like the usual Navajo motifs. Instead of folksy scenes of hogans, sheep, women dressed in rich velvet skirts and turquoise and their men in wide-brimmed hats and boots, Marlowe Katoney’s works depict skateboarders, realistic depictions of Code Talkers, all-seeing eyes beaming outward and the Navajo -tree. of Life with a flock of Angry Birds. Its colors can be dazzling, almost neon-bright, or subdued, like the first glimpses of the sunrise.

Marlowe did not set out to become one of Indian Country’s most unconventional weavers, although he has been interested in the art since he saw his maternal grandmother weaving.

“I was always fascinated by the strings and what they did,” Marlowe said. “But I thought I was going to be a teacher.” He attended the University of Arizona on a scholarship, inspired by native art legends and fellow rebels Charles Loloma, the Hopi jeweler whose work was initially rejected for not being “Indian” enough, and Luiseño painter Fritz Scholder, who never really felt a native felt. Both studied at the UA. Marlowe studied art history, Native American studies and literature, with the intention of switching to painting.

But money ran out and Marlowe struggled to work and attend college. “In the end, it didn’t work out the way I wanted, so I ended up coming home,” he said.

Back in Winslow, Marlowe waited tables at the Turquoise Room at La Posada and worked as a patient registration clerk at the Winslow Indian Health Care Center before turning to the arts full-time. Grandma showed Marlowe the ropes – or strings – of weaving so that he had “something to fall back on.”

Marlowe paints portraits with dyed wool rather than oil, pastels, or watercolor, utilizing his eye for color, his love of popular and Navajo culture, and his formal art training.

Some of his first works were butterflies, ‘three maroon butterflies with blue dots.’

A visit to the RB Burnham Trading Post in Sanders proved to be a turning point as he began his career weaving with vegetable-dyed yarn.

“Sherry Burnham and her husband had seen my weaving and said they saw something in it,” Marlowe said. Her father, merchant Bruce Burnham, had a supply of specially ordered yarns from Britain and Pennsylvania that he wanted to use to revive the Germantown weaving style, and gave Marlowe one skein of each color.

“Let me see what you can do with this,” Bruce said.

Marlowe’s career took off from there. He quickly became known for his unique take on Navajo traditions as well as street skating and raves. In 2017, Marlowe won a Conrad House award at the Heard Indian Fair for breakdance textiles.

Since then, Marlowe has made a name for himself as an eclectic artist. He said he works with both vegetable and aniline dyed yarn to create textiles that look more like paintings than traditional Navajo design.

The “Angry Birds” textile, which is in the Heard Museum collection, was recreated in Lego blocks. In 2023, he also had a one-man exhibition of his work at the UA’s Museum of Art.

After taking a break from the markets, he will be attending the Heard Indian Fair in 2025. “I owe them a lot,” he said.

Marlowe’s younger brother Yancey also works with colored paint and ink. Yancey is a talented muralist whose work brightens the brick and block walls of Winslow buildings.

He brought a reporter and photographer from The Arizona Republic, part of the USA TODAY Network, to a side wall of a cafe and former trading post that he decorated with Navajo, Hopi and Spanish symbolism, including wedding baskets, textiles, Frida Kahlo and a figure that looks like a cross between a kachina and R2D2 from ‘Star Wars’.

Down the street, Yancey showed off his latest work: a mural and painted signage for a new chip shop. He talked about his dreams.

“I want a place off the grid with my girlfriend and a big pickup,” he said, pointing to a huge black four-door truck with big off-road tires. “And I want a studio.”

Yancey said he wants to move his tattoo parlor to larger locations. He rented a corner in an existing tattoo and body piercing shop, but would like more space.

He presented his exacting work in ink in his current space. Yancey carefully guided the needle filled with black ink into the arm of one of his clients and traced the outline of a Greek god on the man’s bicep. The customer would return to have the photo completed once he had saved more money.

Yancey’s wish for her own space will soon come true. Marlowe said the brothers found a studio to rent that they will share.

Debra Krol reports on indigenous communities at the confluence of climate, culture and trade in Arizona and the Intermountain West. Reach Krol at debra.krol@azcentral.com. Follow her on X @debkrol.

Coverage of indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and trade is supported by the Catena Foundation.