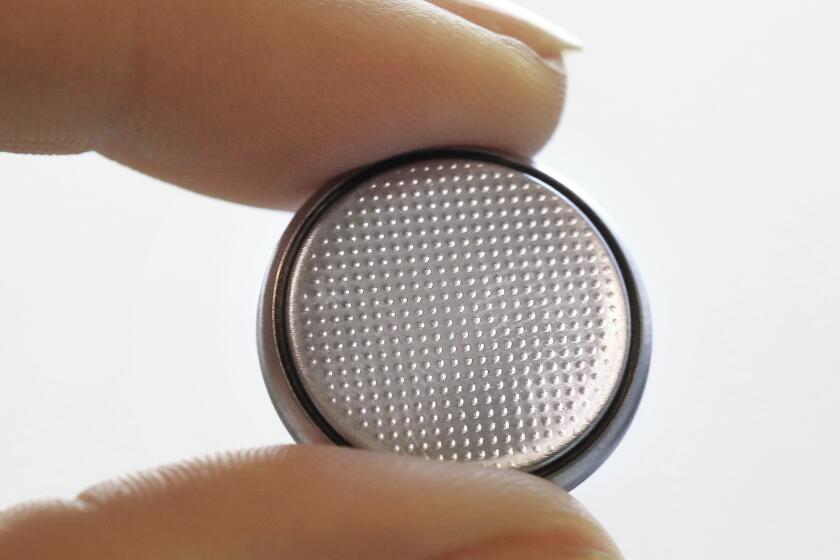

The round batteries, small as buttons and shiny as coins, are prized for the energy they contain in their size. They have become commonplace in households, powering remote controls, hearing aids, toys, electric tea lights, wristwatches, greeting cards that play music and other familiar objects.

But doctors warn that such ‘button batteries’ can maim and kill. Put one in your mouth and swallow it – as thousands of children do every year – and they can quickly cause devastating injuries.

A growing number of medical associations are urging battery manufacturers to confront the threat by creating a new product: a button or “button cell” battery that will not cause catastrophic injuries if swallowed.

“The only real solution to the battery problem is to make the battery itself safer,” says Dr. Toby Litovitz, founder of the National Capital Poison Center.

When button batteries enter the body, their electrical current breaks down water, raising alkalinity to dangerous levels similar to bleach. Body tissues can liquefy. Doctors say serious injuries can occur within two hours, sometimes before a parent realizes a battery has been swallowed.

As button batteries become more common in common items, the number of pediatric emergency visits for battery-related injuries has more than doubled in recent decades, according to a study published in the journal Pediatrics. Some children ended up relying on tubes to breathe or suffered massive bleeding, doctors said.

“Unfortunately, these batteries cause such serious injuries so quickly,” some of which are impossible for surgeons to repair, said Dr. Kris Jatana, surgical director of clinical outcomes at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

Jatana became alarmed by the risks after caring for a 2-year-old child who ultimately required a tracheostomy to breathe. “It was a moment that motivated me to try to see what we could do to prevent these injuries in the first place.”

Some battery manufacturers have tried adding a bitter coating or a saliva-activated dye to warn parents.

Reese’s Law, a federal statute named after a child who died from serious injuries after swallowing a coin-cell battery, now requires that compartments for such batteries in consumer products be more difficult to open and mandates child-resistant packaging for coin-cell batteries.

But advocates say more needs to be done. For example, Litovitz said that harder-to-open packages don’t address the many injuries caused when children swallow batteries that are left or thrown away. Among those pushing for the development of safer batteries is biotech entrepreneur Bryan Laulicht.

“What makes them really great for devices is also what makes them so dangerous if you swallow them,” Laulicht said of button batteries. “They are powerful enough to split water… raising the pH to Drano levels within minutes.”

Doctors began raising the alarm about the threat decades ago, as more and more children began suffering serious injuries. One study found that between 1985 and 2009, the percentage of button cell batteries that led to serious or fatal injuries increased more than sixfold.

Litovitz and other researchers pointed to the rising popularity of the 20-millimeter-diameter lithium coin cell battery: their analysis found that 12.6% of children under the age of six who swallowed button batteries of about that size experienced serious complications or death members.

They are “just the right size to get stuck in the esophagus of a small child, especially one under the age of four,” Litovitz said in an email. “Plus, these lithium button cells have twice the voltage of other button cells.”

Doctors may not recognize and diagnose the problem immediately if no one realizes that a battery has been swallowed, as the symptoms may initially resemble those of other childhood diseases.

The problem has worsened over time: From 2010 through 2019, an average of more than 7,000 children and teens went to emergency rooms each year for battery-related injuries, according to the Pediatrics study. The number of such emergency visits had doubled compared to the period 1990 to 2009.

Coin batteries were involved in the majority of cases where the battery type was known. Researchers have tallied more than 70 deaths over time from ingesting button cell batteries, but Litovitz said the actual number could be much higher because that figure only includes cases documented in medical research or in the media or were reported to the National Battery Ingestion Hotline, which stopped operating six cases. years ago.

At Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, doctors see about one child per month injured by a coin cell battery, said Helen Arbogast, injury prevention program manager in the department of pediatric general surgery. Children are attracted to shiny things and pick up on the attention adults pay to electronics, she said.

“Remotes are really fascinating to them — the buttons, the colors — and part of their natural motor skill development is learning to open and close things,” Arbogast said.

She emphasized that time is of the essence. “If a parent suspects their child has swallowed a button cell battery, it is important to take them to a hospital right away.”

In Texas, Reese Hamsmith woke up constipated and wheezing one morning in 2020. Her mother, Trista Hamsmith, took the toddler to the pediatrician, who suspected croup. It wasn’t until the next day, after a Halloween night when Reese had remained ill, that her mother realized that their remote was missing a button battery.

Reese underwent emergency surgery, but the damage remained even after the battery was removed, burning a hole in her esophagus and windpipe, her mother said. In the weeks that followed, she underwent more surgeries, anesthesia and intubation. Less than two months after her injury, Reese died.

She was one and a half years old. After her death, “I held her again and promised her that I would do everything I could so no more child would die like this,” Trista Hamsmith said.

The Lubbock mother started a nonprofit, Reese’s Purpose, which successfully pushed for federal legislation imposing new requirements for battery compartments, child-resistant packaging and warning labels. Hamsmith was pleased when those rules came into effect, but regretted that such protections had not been put in place sooner.

“It shouldn’t take what we’ve been through” to spur action, she said. “There should be absolutely no need for someone like me to shout at the world.”

The group is also funding research into a medical device that can detect a swallowed battery without exposing a child to radiation. Hamsmith wants it to be used when a child is showing possible symptoms. And it worked with Energizer on safety features, including a telltale dye that turns blue with saliva.

“The missing ingredient here… is the ability to alert the healthcare provider that something has happened,” said Jeffrey Roth, Energizer’s global category leader for batteries and lamps. “That’s basically what ‘color alert’ does: it alerts the caregiver that a child may have put something in their mouth that they shouldn’t have.”

However, Litovitz cautioned that because not all batteries have the blue dye, doctors and parents should not assume a battery has not been swallowed if they do not see that color.

Roth said Energizer has spent tens of millions of dollars in recent years on research and other efforts related to button battery safety. “We believe that one day we will solve this,” he said. “But it certainly requires breakthrough innovation.”

Laulicht, co-founder and CEO of Landsdowne Labs, said his company has tested an alternative battery with a different type of casing, intended to be disabled inside the body. Tests that sandwich the battery between two pieces of ham do not show how much damage is done by commercially available button cell batteries, he said. (Ham is used as a readily available substitute for human gastrointestinal tissue, Laulicht explained.)

One of their challenges is getting the same level of battery performance with these changes, Laulicht said. But as a father of young children, ‘I would prefer [have] a battery that only lasted a year on the shelf…but didn’t kill my child when they swallowed it.”

Sign up for Essential California to get news, features, recommendations from the LA Times and more delivered to your inbox six days a week.

This story originally appeared in the Los Angeles Times.